In Hinduism great emphasis is given to visual interaction between deity and worshippers. Devotees wish to see and be seen by the gods, and believe that they will be benefited by doing so. Underlying this belief is a conception of "seeing" as an extrusive flow-of-seeing that brings seer and seen into actual contact. Under the right circumstances devotees are thereby enabled to take into themselves, by means of vision, something of the inner virtue or power of the deity, including the deity's own power of seeing. Evidence in support of this thesis is drawn from three sources: two modern reli- gious movements and a popular religious film.

Let's start by establishing the context of my problem. A fact that is obvious to anyone familiar with Hindu life is that Hindus wish to see their deities. This is, indeed, a fundamental part of what the worship of a deity's image (murti) is all about. At a minimum one goes to a temple to see, to have the darshan (sight) of, the deity housed within. Deities sometimes emerge from their temples in procession, as kings and queens might come forth from their palaces, so that they may see and be seen by their worshipper-subjects. Moreover, short of temple visits, there are always pictures. Even though colored prints of deities may be relatively new on the Indian scene

(Basham 1977:ix), there is hardly a more ubiquitous feature of Hindu life today. Virtually everywhere Hindus live or work there are pictures of the gods.

Nor are deities found only on altars or in pictures. They can also live among their devotees in the form of deity-gurus, religious preceptors who are commonly regarded as divine incarnations. Followers of a guru ardently desire his darshan, which he grants to his devotees as a sign of his favor and grace. Around this has grown a vigorous tradition of "photo-iconography," in which photographs of gurus are kept and venerated by their devotees. The visages of these living gods are every- where around their followers: in lockets, wallets, rings; on walls, both at home and at places of work. Sathya Sai Baba, probably the most famous of the living gurus, materializes (among other things) pictures of himself for his favored devotees, and his photographs are said sometimes to exude honey or vibhuti (cowdung ash), signs of his grace, and media through which his power is transmitted.

But if it is clear that Hindus want to see their deities, there is another important point that may be less obvious; Hindus want to be seen by their deities as well. Per- haps nothing indicates this more clearly than the iconographic importance given to eyes. Even the crudest lithic representations of deities are likely to have eyes, if nothing else in the way of facial features. Eyes, moreover, are associated with the life of the image, so that the consecration of images is, in part, accomplished by the creation or opening of its eyes (cf. Eck 1981:5-6, 40). The implication is that if the deity is present, the image sees. Great emphasis is likewise given to the eyes of the living deities, the gurus. Devotees long for their guru's gaze to single out and light on them, and the photo-iconography of the gurus frequently emphasizes and accentuates face and eyes.

Hindu devotees, then, wish to see the gods; and the gods evidently see their devotees in turn. My question is, what does this mean? What is actually believed to be going on in these visual exchanges between deities and their human worshippers? What I shall try to establish is that in the Hindu milieu seeing is believed to have good and bad effects on that which is seen, and that one of the purposes of worship is to attract to the devotee a deity's benevolent gaze. I shall further suggest that visual interaction between deity and worshipper establishes a special sort of intimacy be- tween them, which confers benefits by allowing worshippers to "drink" divine power with their eyes, a power that carries with it-at least potentially-an extraordinary and revelatory "point of view." The evidence on which my analysis is based comes from three sources: two modem Hindu sects and a popular religious film.

Each of these gives heightened emphasis to a different aspect of visual interaction.

THE GLANCE OF COMPASSION: THE RADHASOAMI GURU The sacred literature of the Radhasoami sect, a religious movement founded in Agra in the mid-nineteenth century, abounds with poetic images of the "glances" exchanged by gurus and their followers. The ethnographic use of devotional poetry is, I believe, especially appropriate in the present context. In this poetry there is an attempt to describe certain aspects of Hindu ritual as "internal" experiences, involving extraordinary explicitness about matters that are more often left to impli- cation. This includes some extremely revealing material pertaining to seeing and being seen.

I must first note that the Radhasoami movement was founded by a religious visionary known as Soamiji Maharaj, who taught a method of attaining salvation by linking one's spirit (surat) to a spiritual sound-flow (shabd) which emanates from, and under the right circumstances will draw the spirit to, the Supreme Being, known as Radhasoami. The linkage is accomplished by means of an esoteric form of spiritual exercise known as surat-shabd-yoga, which was given to humanity by the Supreme Being, who incarnated himself in human form in order to impart it. The first of these incarnations was, of course, Soamiji Maharaj. The question of who the others were, and are, is in dispute, but all the existing subsects agree at least on this: that salva- tion cannot be attained without contact with a sant satguru. The complete centrality of the guru is probably the single most important point of Radhasoami doctrine.

Radhasoami teachings place the strongest possible emphasis on seeing, and being seen by, a true guru. Indeed, in Radhasoami doctrine this is a necessity for salvation; an internal visualization of the guru is a vital step in embarking on the road to salva- tion. Therefore, one should seek a true guru's darshan; when one sees a true guru one feels a surge of spiritual emotion inside. Thus, when a guru passes by, his followers gaze at him in hopes of provoking inner experiences. When Maharaj Charan Singh

(satguru of the Beas subsect) visits Delhi, thousands of devotees obtain his darshan by filing by his seat in ten continuously moving lines. Nor need the guru be physically present to grant darshan; in his absence, pictures of him preside over congregational gatherings. Dreams and waking visions of gurus are common among Radhasoami devotees, and are greatly valued as signs of grace. It is believed, moreover, that at the time of death every true devotee has his guru's darshan. It is sometimes said that one of the distinguishing characteristics of a true guru is that when large congrega- tions are before him he seems to be gazing at each devotee personally. And it is also said that when he looks at the devotee he "sees everything" within.

VISUAL INTERACTION IN HINDUISM It is therefore not surprising that when we turn to Radhasoami sacred literature, we find a rich visual imagery, and this is especially true of the poetic compositions (the Sar Bachan Radhasvdmi, Chhand Band and Prem Bzni) of the founding guru and his immediate successor. One of the first things that becomes apparent upon pe- rusal of these works is that the matter of what takes place visually between devotee and guru is given special emphasis in relation to the Radhasoami version of the Hindu rite known as drati.

In general usage the term refers to a ritual sequence associated with piuja (wor- ship), in which the officiant circles a lamp (and sometimes other objects) before an image of a deity. While this takes place bells are rung, and those present often sing special arati hymns. In the Radhasoami group I know best (the Soamibagh satsang, who at present have no living guru), arati used to be performed as an actual cere- mony, in which a congregation sang arati hymns before the guru, while gazing into his eyes. But even then, as now, arati was regarded as essentially an internal occur- rence, associated with the contemplation (dhyan) of the guru, to which the outer ceremony was at most only a kind of provocation and crude guide. One closes one's eyes and concentrates on the "form" (svarup) of the guru, especially the eyes, in effect sublimating the ceremony into mental images.

In the Radhasoami arati hymns a number of aspects of the rite are portrayed. The devotee is described as prepared to perform arati, "adorned" for the occasion and beautiful in appearance. But since the real significance is internal, the parapher- nalia are aspects of the devotee's own being: "My body and mind are the platter, my longing the lamp" (Sdr Bachan:6(3)2). As in an ordinary act of Hindu worship, a food offering is present, but this too is inward: "I made a bhog [food offering] of my devotion. I sang of my contemplation" (S.B. 6(12)3). Above all, however, the devotee sees his guru: "I got guru's darshan and sang his glory. I took into my eyes his incomparable appearance" (S.B. 5(5)3). The devotee is swept away by the vision: "Every moment my love increases. The image of the guru looks marvelous./ I lose my eyes and breath. I lose my sense of body and mind./ . . . to it [guru's image] I am as the chakor [a moonlight-drinking bird] to the moon" (S.B. 6(2)19-21).

According to the poetry the experience of arati is a kind of journey, an internal pilgrimage. The specific details of Radhasoami cosmology need not detain us, but I must note that it is based on the idea that there are many levels in the universe above the plane we inhabit, and that these are accessible through an aperture between the eyebrows known as the tisra til, the "third eye." The highest of these is the "abode" of Radhasoami, and this (our "true home") is the goal of the devotee's inner journey. In the arati hymns the conception of the journey is both acoustic and visual; on his way upward the pilgrim sees the sights and hears the sounds character- istic of each level. He first takes his "seat" at the tisra til; there he has darshan of his guru. He sees a flame and hears the sound of a conch and bell. His spirit is caught by the current of shabd, and in the company of his guru he is pulled upward. He sees marvelous sights-suns, moons, skies beyond the sky, and more-and he hears the sounds of bells, thunder, musical instruments, and of things quite unlike anything we know in this region. He also has visions of the deity (dhani; wealth-holder, lord) who presides over each of these celestial levels.

Implicit in this imagery, I think, is the suggestion of a change in the devotee's own power of seeing-the universe, and especially the guru, come to be "seen" in a new and spiritually significant way. The devotee begins by seeing the familiar form of the guru, and then sees the forms of the presiding deities of the universe, each higher than the one before, and their various realms as well. At the end of the journey he has the darshan of Radhasoami himself, the object of his pilgrimage. This is truly the climactic vision. The beauties and grandeur of his "abode" transcend everything seen before. The form of Radhasoami " . .. is without limits and beyond description./ To what could I compare it? It is beyond all measure" (S.B. 5(2)35-36). The point seems to be that the devotee's own visual power has in some sense been altered, increased, augmented-which may explain the poet-devotee's curious asser- tion that he has acquired a durbin, a "telescope." The devotee sees as he could not see before, and a wholly new universe comes into view. Most important of all, how- ever, he now sees his guru as he truly is; that is, as the Supreme Being. This is the fulfilling darshan, and the devotee has now come to the end of his journey: "I have gained a dwelling place in the feet of Radhasoami. Pure bliss is now forever mine" (S.B. 6(8)26).

theme that runs alongside this celebration of the expanding spectacle of the world and illuminated vision of the guru. Not only is the guru seen by the devotee, but he, in turn, sees the devotee in a very special way. "We join glances as I stand facing him," says the poet-devotee, and "Satguru casts on me his glance of compassion (divya drishti)" (S.B. 30(4)5). This seems to be the heart of the matter. Devotee looks at guru, and guru looks back; the glance that the guru casts upon the devotee is one of "compassion" or "kindness" (the Hindi words daya, kripa, and mehar are used interchangeably in this context). Furthermore, it is appar- ently because he is looked at in this way that the devotee is able to achieve his goal; that is, to achieve right concentration and move upward to regions beyond: "Guru cast his glance of kindness on me," the poet says, "and my mind became engaged in meditation (dhyan) and shabd" (Prem Bani, 8(21)3). Elsewhere the devotee pleads for his guru's assistance, saying "give me your glance of kindness [here kripa drishti] and swing me [upward]: Then the power of [mere] intellect (buddhi) will vanish" (S.B. 30(2)7).

This idea, that the drishti, the "seeing," or "glance," of the guru aids the devotee in achieving his deliverance, seems to be a crucial aspect of the Radhasoami under- standing of what is supposed to take place visually between guru and devotee. The essential idea is expressed succinctly in a prose passage in S&r Bachan: the devotee, the author says, should have the darshan of the guru for a couple of hours; that is, "with his eyes he should gaze at [satguru's] eyes." The devotee should try to increase the duration of this every day, "and on that day that [satguru's] glance of mehar [compassion] falls on you, your heart will be instantly purified" (S.B. 21(3)6-14). In other words, by joining gazes with the guru, the devotee can gain access to a be- nevolent power that apparently emanates from the guru's eyes.

The arati of the poet-devotee is essentially a transposition of a common Hindu ceremony onto an internal landscape, and it tells us more than we are usually told about the rite itself, and about the glances exchanged between men and the gods. The poet presents us with a conception of arati; one of the things he considers it to be is an occasion for what psychologists call "gaze fixation." The worshipper sees an inner flame and hears a bell and conch (soteriologically significant, but also prob- ably corresponding to the real flame, bell, and conch in an actual outer ceremony), but above all he sees-and is seen by-his guru, who in this context takes the place of the image of the deity in a normal arati. Their gazes "unite" ('ornd) and "mix" (milna), and the devotee's spirit is "drawn up."

In other contexts, particularly in the prose discourses of the Radhasoami gurus, these images are linked with a more explicit theory of vision. There is a "current of sight" (drishti ki dhar), a fluid-like "seeing" that flows outward and downward from the tisra til to the two eyes, and from there out into the world. The devotee's object is, by "turning" the pupils of the eyes, to "reverse" this current (along with other currents), to disengage it from worldly objects, and to pull it back up to the tisra til, from which point it is caught and taken to still higher regions. In the poetry the devotee is portrayed as being drawn upward into a vision. He sees his guru and more; and what he sees is beautiful, remarkable, splendid: it pulls at his inner sight and concentrates his attention. He finds himself on a pilgrimage of insight; he sees, and then learns to see in a new way. But as he sees he is seen, and it seems to be his guru's glance of benevolence that ultimately enables him to reach his goal. It is as if by "mixing" his sight with his guru's superior sight, he comes to see better-is "pulled" or "taken" upward and inward by his guru's "flow of seeing." The apparent paradox, that seeing in some way "takes" as it "flows forth," is apparently not perceived as such. A "current," the Radhasoamis sometimes say, is like a "wave" (lahar) which, as it recedes, leaves particles of itself behind, only to reclaim them on the next surge. In any case, this mingling of "seeings" results in a visual consummation. As the dev- otee comes to see the deity-guru as he "really is," he is seen in a way that confers benefits and effects a kind of self-transformation. The point seems to be that one is "seen beneficially" by "seeing" an exalted being in the right way.

But might one be seen by a deity in a different way? Are there other kinds of "glances"? And is there a wider cultural context for the whole question of glances and their meaning? In order to consider these questions I must move to a very differ- ent kind of evidence.

THE GLANCE OF ANGER: JAI SANTOSHI MA Putting movie cameras in the hands of informants has already been suggested as an ethnographic technique (see, e.g., Bellman and Jules-Rosette 1977). The idea is not a bad one: the indigenous cinematographer will presumably turn his camera onto what he regards as significant and thus worth recording, and the result is bound to reveal basic cultural assumptions. With regard to India, moreover, we do not actually have to give our informants cameras, for cameras have already been in the hands of indigenous film makers for many decades. The vernacular movie is a rich and greatly underutilized source of cultural data.

The film with which I am concerned, Jai Santoshi Ma, is probably one of the most important and successful Hindi religious films of all time. It even has the dis- tinction of being the inspiration for a popular religious cult (that of the goddess Santoshi Ma). The plot need not concern us. What is of interest is the fact that the film includes scenes of deity and worshippers confronting and interacting with each other, and when this happens the camera not only gives us a close and informed look at what is taking place, but also, by taking the perspectives of the participants, gives us an indication of what the participants themselves are supposed to be seeing. In other words, the film presents us with what its makers and viewers regard as plausible worshippers'-eye views of the goddess, and goddess's-eye views of the worshippers.

Let us begin by examining a scene in which interaction between the goddess and her worshippers is occurring "normally," that is, in which both parties are behaving as they should. Near the opening of the film we find ourselves watching a kind of Hollywood version of the arati rite, apparently taking place in a temple. We see women singing and dancing before the goddess as they hold offering trays aloft. While they dance they gaze at the goddess, and when the camera turns to the goddess we see what they see, namely, an image of the goddess looking downward at us. Our attention-presumably reflecting theirs-is drawn especially to the goddess's face, which appears at the bull's-eye of a large, rotating disc. When the camera shifts to the goddess's perspective, we find ourselves looking downward at the worshippers who, in their turn, are gazing back at us. Much else is going on in this scene, but one important facet of the situation is that goddess and worshippers are looking at each other. And as the goddess surveys this gay scene, all is as it should be; her glance is evidently benign.

But her glance is not always benign. In the climactic scene of the film the goddess is again being worshipped. This time, however, one of the wicked sisters-in-law of the heroine tries to thwart the ceremony. Knowing that nothing sour should ever be given to Santoshi Ma, she squeezes lemon juice into milk that is being offered to the goddess; the goddess reacts. The camera turns not to her image, but to Santoshi Ma herself, in her heavenly region, and we see that she is very angry. The camera shifts back to the locale of the ceremony, and we see the house being swept away by an earthquake and storm. Once again we see the goddess, and from her eyes comes fire that burns the bodies of the wicked sisters-in-law.

But matters do not end here. In the midst of all the destruction, the heroine collapses pathetically at the goddess's altar and begins to sing a song of prayer. The camera turns to the goddess's image, and then to the goddess herself in heaven; the anger is beginning to leave her face. Now we see the heroine looking up at the goddess, eyes flooded with tears. The goddess relents. The storm ceases, the house is magically put to right, and the burns disappear from the bodies of the sisters-in- law. The goddess now personally appears on the scene, the heroine crumpled at her feet. All cry out "jai Santoshi Ma" (victory to Santoshi Ma) and make obeisance: all is once again as it should be.

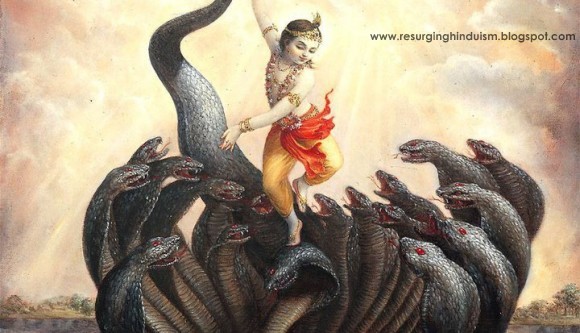

These details have one obvious implication concerning the "glances" of deities: a deity's glance is not only potentially beneficent, but can also be destructive. As the film makes abundantly clear, Santoshi Ma's glance is not necessarily one of "kindness" or "compassion." She can bring blessings to her worshippers, but she can also cause great harm; and in this instance, at least, we see that her destructive power comes from her eyes. Here is the apparent opposite of the "glance of kindness" of the gurus in the Radhasoami tradition. It is not the only possible example. Shiva's third eye reduced the God of Love to ashes, and will consume the whole world in fire at the end of the cosmic cycle. A deity's eyes can be dangerous.

This, however, should not surprise us, for the eyes of human beings can be dan- gerous, too. The evil eye is a frequently noted feature of Hindu life, based on the assumption that a person who is envious, or in some other way ill-disposed, can inflict harm, usually inadvertently, on persons or objects, merely by looking; that seeing them enviously can somehow extract their valued characteristics (for numerous examples see especially Maloney 1976). The most important condition of vulnerability seems to be the desirability, attractiveness, or power of the person or object in question. Things that are new, beautiful, or valuable tend to attract the evil eye; and thus, for example, in northern Indian cities it is common to see anti-evil-eye slogans painted on new vehicles. Even in upper-middle-class urban neighborhoods one can see spotted pots displayed before newly built houses, to ward off evil glances.

The point is that in the Hindu world, "seeing" seems to be an outward-reaching process that in some sense actually engages (in a flow-like way, according to Radha- soami teachings) the objects seen. Therefore glances can affect the objects at which they are directed, and bad glances can have harmful effects. The evil glances of human beings are not, so far as I can determine, seen as "fiery," but there is nonetheless a possible connection between divine and human ocular aggression, at a deeper level. In an extremely illuminating analysis of the evil eye in Indo-European and Semitic cultures, Alan Dundes (1980) has produced extensive evidence suggesting that under- lying the phenomenon of the evil eye is a kind of "liquid logic." This arises from an image of human good as limited in quantity and fluid in nature; thus, one person's prosperity is gained at the expense of the life-giving and supporting fluids (blood, milk, semen, etc.) of less fortunate others. The evil eye "drinks in" the liquid source of the vitality, strength, or beauty of the victim, resulting in a kind of "dessication," of which withered crops and milkless cows are prime examples. Thus, in India one is told that it is especially the (milk-nourished) plumpness of infants that is the "beauty" which attracts "glances." Fire, the medium of Santoshi Ma's destruction, and Shiva's too, dessicates; it harms by drying out. In this connection it may be noted that Shiva is, as the fieriest of the gods (in one of his phases), apparently the thirstiest as well. Fundamental to Shiva worship is the act of pouring water or other fluids over the lingam. Dundes suggests an association between eyes and genitalia (1980:113-19); if this is correct, pouring water over the phallic lingam could be an appeasing replenishment of the fluids of Shiva's dessicating third eye.

In any case, the fact that glances are believed to have potentially bad as well as good effects on their targets must necessarily shape the ways in which human beings approach and deal with the gods. As the Radhasoami evidence suggests, "uniting" glances with a deity can be beneficial. Therefore devotees wish to see, and to be seen by, the gods. But glances, both divine and human, can be harmful, and we must there- fore assume that measures are necessary to control eyepower-to ensure that the glances exchanged are benign.

However, the question of the control of potentially harmful glances between deities and humans presents us with an apparent puzzle, centering on the question of display. As we have noted, the concept of the evil eye is closely associated with envy. This being so, to avoid the evil eye one should become inconspicuous; one should maintain a "low profile" by avoiding display of that which will excite the envy of others. One must always be careful lest someone "look"; and thus what one wants, in a sense, is not to be seen. But in a ritual setting it is exactly the op- posite. Here, of course, the whole point is to be seen: for worshipper to see deity, and for deity to see worshipper. Consistent with this goal, display is strongly emphasized; worshipper and deity are made beautiful for each other. Instead of suppressing glances, the setting is one that encourages them. Given the logic of the evil eye, this means that the ritual situation is one of heightened vulnerability to harm through glances, and this would presumably apply to deity and worshipper alike.

This analysis may explain why gaze fixation seems to be a special feature of arati, or more probably, why arati is a special feature of gaze fixation. The main gesture of arati, the circling of the lamp, is (as part of a complex of meaning) asso- ciated with protection, and this includes protection from the evil eye (Maloney 1976: 123-25). Its efficacy is probably connected with an idea of "tying" or "binding" potentially degradable or stealable virtues by means of the circular motions (Marriott, personal communication). The powerful, the exalted, the beautiful, are natural tar- gets for the evil glance of envy, and therefore deities need to be protected, especially when they are being worshipped and thus "adorned" and exposed to public view. It is at the moment when glances are "joined"-that is, at the moment that the visual channels are most open-that the deity would be most vulnerable to harmful glances, and therefore it is at this moment that the arati gesture is most appropriate. A very similar circumstance arises in marriage ceremonies: bride and groom are made beautiful, and thus they attract glances; they are supposed to be looked at. There- fore, arati is performed for them, which is to say, they have become as vulnerable as god and goddess.

But what of the potentially harmful glances of gods? What might provoke such glances, and what prevents them? Here matters are far from clear. It is not, of course, at all obvious that envy should be a factor in the deities' regard for men. It is for the low to envy the high, not the other way around. Evidence from the film Jai Santoshi Ma, however, suggests a possible interpretation. What we see in the film is that the provocation of the goddess has something to do with ignoring the proper ritual re- quirements of her worship. Santoshi Ma will not tolerate sour things, as the wicked sister-in-law well knows. But I think more is involved than a mere ceremonial lapse. What the film makes plain is that it is the heroine's devotion that converts the god- dess's bad power to good power, and this devotion is primarily seen in the heroine's complete submission. It is when she surrenders to the goddess, when she falls at the goddess's feet, that the transformation of the goddess's disposition occurs. This suggests that the sister-in-law's real sin was lack of submission as expressed in her defiance. She knows that the goddess does not tolerate sour things, but performs the fatal adulteration anyway. She is defiant in the sight of the goddess, and the result is a glance of wrath.

George Foster (1972) reminds us that there is a crucial distinction between envy and jealousy, even though they tend to be confused in normal English usage. Jeal- ousy is the natural reciprocal of envy; one is jealous of that which one is envied for. It may then be that if the envious glances of men are dangerous to the gods, it is (in the psychology of worship) the jealous regard of the gods that is most dangerous to men, an idea which could conceivably arise from "projection" of the worshippers' own envy of the gods (Dundes 1980:100). And if the gods are jealous of their suprem- acy over men, then submission is the obvious antidote.

The question of submission and surrender draws us downward from the eyes to another and equally important feature of divine anatomy: the feet. It is scarcely possible to exaggerate the importance of foot imagery in Hindu religious thought. Devotional literature celebrates the god's feet;just as one wishes to see the god, one wishes to touch the god's feet. Deities are sometimes represented iconographically by their feet, and the photo-iconography of gurus strongly emphasizes feet. Devotees of Sathya Sai Baba keep plaster casts of his feet in their homes as objects of worship. In fact, there is a particular photograph of Sai Baba, one frequently seen in the homes of devotees, that seems in itself to be a kind of lesson about divine feet. In the picture the saint stands erect with his hands behind his back, a nearly featureless saffron column. At the top is his face, greatly accentuated by his halo of long, frizzy, black hair. Down at the bottom of the column, just peeping out from under the fringe of his garment, are four divine toes. The picture is an invitation. It allows the devotee a glimpse of, and invites him to touch, the lord's feet. The picture thus portrays an act of grace, because in offering his feet to be touched, the saint is also offering his divine protection.

themes in Hindu devotionalism is that of "protection," or "shelter" (saran). What the devotee seeks is the god's shelter, and as Susan Wadley (1975) has pointed out, this idea falls within the more general paradigm of relations between the powerful and their dependents in Hindu society. One is under the pro- tection of parents, jajmand patrons, and the gods as well. The importance of feet in religious imagery is that they symbolize this powerful idea. One touches the feet of protectors, of the great and powerful, and in so doing signals one's own submission and surrender. Moreover, the gesture suggests reciprocal obligation; he who has been surrendered to, and who has accepted this surrender, is obliged-on the model of the parent or patron-to provide shelter and protection to the one who has surrendered. This is sometimes acknowledged in a gesture of blessing, in which the superior party signals his acceptance by gently patting the head or shoulder of the foot toucher with his hand. It is possibly for this reason that the right hand of a deity is often represented as a source of his or her benevolent power. As an organ of the acceptance of another's submission, it is a point of concentration of power-of-protection.

To the surrendered devotee the deity's feet are therefore worthy of attention, praise, and, above all, physical contact. To him they are an opportunity for intimate humility, an idea deeply imbedded in patterns of "flow" exchange which Marriott (1976) has shown to be characteristic of practically every aspect of Hindu life and thought. The feet (along with other parts of the anatomy, especially the mouth) are sources of downward and outward currents of inferior matter (i.e., inferior relative to its source), and by taking this onto and into himself the devotee is expressing humility by receiving from his lord, and treating as valuable and "pure," that which is ostensibly base and "impure." But at the same time he is establishing intimacy, and even identification, by taking something of the deity into himself. In fact, he is internalizing his lord's "power" and "value," because to the surrendered devotee such "flow" really is powerful and valuable, since the very act of taking it, as a ges- ture of surrender, invokes on his behalf the deity's power-of-protection. In other words, the "drinking" (Dundes 1980) of a deity's virtue is indeed possible in the Hindu world, so long as it is done from below. Whereas evil glances steal valuable fluids, this is innocuous drinking, for the devotee takes only the inferior stuff that the deity discards. Therefore, the devotee looks at his washes them. And he drinks the water in which they have been washed, for in the context of his surrender this water is the purest nectar (charanimrit, "foot-nectar") and a medium of beneficial power.

To return briefly to the Radhasoami movement, there is hardly a stronger theme in their poetic literature than that of the guru's feet. By worshipping his feet one banishes "egoism," one becomes his "slave" (kinkar), and this is the key to his pro- tection. "Worship no one but guru," the poet says, "Have his darshan and serve his feet" (S.B. 16(1)17). "I looked to his feet," the devotee says, "I obtained shelter, I adorned myself with shabd" (S.B. 6(21)2). The devotee takes the flow that comes from his guru's feet (and mouth, too; the same principle is involved) into himself: "I lick his feet with my tongue" (S.B. 3(5)40), and "I serve his feet, I drink his foot-nectar. In ecstasy I take his prasad [food leavings] " (S.B. 6(15)19). In the end, the guru's feet turn out to be the ultimate goal itself. "My task is now finished," the devotee says, "I am the dust of Radhasoami's feet" (S.B. 5(4)28).

Our main concern is not feet but eyes. But to understand divine eyes we must understand the feet-or rather what they symbolize-as well. It is not a matter of feet in themselves, but of ideas they powerfully evoke in the Hindu world. How is it that the gods come to look kindly on their human worshippers? The answer seems to be that it is above all surrender that invokes the "glance of compassion." There- fore, it is at, under, and even within the lord's feet that shelter is to be found, and in this sense to touch his feet is to control the power of his eyes. More simply, if one wishes to be seen beneficially by a deity, one had better be below the deity.

THE GLANCE OF TRANSFORMATION: THE BRAHMA KUMARIS But why is looking important? Having the darshan of a deity is clearly regarded as beneficial to a devotee, but what exactly is the nature of the benefit? At one level, of course, there is little problem; if looking "takes," as it appears to, then looking at a superior being benefits the looker. But this does not exhaust the matter. Icono- graphic traditions, Radhasoami poetry, and even the camera angles of Jai Santoshi Ma all suggest that not only do worshippers look at the gods, but the gods look back. Worshippers see and are seen by the deities; there is a visual transaction involved, and this is the heart of my problem.

From the materials we have looked at thus far, it is evident that an important theme in Hindu worship is that of "closure" between deity and worshipper; the dev- otee surrenders through intimacy, and establishes identification with the deity by taking something of the deity into himself. In a rather special sense, the worshipper "drinks in" the deity, but only, as we have seen, from below. I would now like to suggest that seeing and being seen is a special (and perhaps the highest) medium of intimacy between deity and worshipper. It is another type of flow taking, in which the beneficiary mingles a superior, apparently fluid-like "seeing" with his own, thereby appropriating its powers.

In the Hindu world "seeing" is clearly not conceived as a passive product of sensory data originating in the outer world, but rather seems to be imaged as an extrusive and acquisitive "seeing flow" that emanates from the inner person, outward through the eyes, to engage directly with objects seen, and to bring something of those objects back to the seer. One comes into contact with, and in a sense becomes, what one sees. To see a deity is therefore beneficial, but to see a deity as one is seen by that deity is especially beneficial, because it allows the devotee to take in, in a manner of speaking to drink with the eyes, the deity's own current of seeing. This is a flow, or current, of extraordinary virtue; because of its origin in the inner and upper recesses of the deity, it allows the devotee to acquire something of the deity's highest nature. Under the right circumstances, then, seeing and being seen by a deity is valuable because it permits the devotee to gain special access to the powers of a superior being.

But I think even more is involved than this. If seeing itself is carried outward as flow, then what the gazing devotee is receiving, at least by implication, is an actual exteriorized visual awareness, one that is superior to his own. This means that quite apart from its more general benefit-bestowing characteristics, darshan has important potential soteriological implications, for by interacting visually with a superior being one is, in effect, taking into oneself a superior way of seeing, and thus a superior way of knowing. Given the premises of the system, this makes available to the devotee the symbolic basis for an apprehension of himself as transformed. Since he himself is an object of his lord's seeing, by mingling this seeing with his own he can participate in a new way of seeing, and thus of knowing, himself.

In order to illustrate the meaning of this, let us take the case of the Brahma Kumaris, a moder religious movement belonging mainly to urban northern India. This small sect is probably atypical in the extreme emphasis it gives to the "joining of glances," but I think that this very one-sidedness affords a unique clarification. To avoid being waylaid by details, suffice it to say that although the Brahma Kumaris do engage in some ritual activities, their ceremonial life is completely overshadowed by the practice of a form of meditation directly connected with their concept of salvation. They believe that the world is soon to be destroyed, and that afterwards a new cosmic cycle will ensue, in which certain highly worthy souls will be reborn to rule as gods and goddesses. The object of the Brahma Kumaris is to be reborn as the deities in this world to come. One of the main ways of attaining this object is the practice of what they call raj yog; it is mainly with this form of meditation and the techniques by which it is taught that I am concerned here.

The goal of raj yogis to realize one's true self. According to the Brahma Kumaris we do not know who we really are. We think we are the bodies we inhabit, but actu- ally we are souls (atma)-massless points of pure brightness and power. The purpose of raj yog is to develop an awareness of ourselves as bright and powerful souls, which awareness will deliver us from false self-understanding and prepare us for our careers as deities in the world reborn.

What is important for present purposes is that raj yog turns out to be an intensely visual experience, and one that involves "glances." It is usually taught to small groups or individuals. The student or students sit in a semidarkened room facing the teacher (usually a woman). Just above and behind the teacher's head is a red plastic ovoid that glows from a lightbulb within; in its center is a tiny hole, which appears as a point of intense white light against the red glow. This device represents the Supreme Soul (known as shiv baba), who is the presiding deity of the universe. With devotion- al songs playing softly in the background, student and teacher gaze intently at each other, either in the eyes or at the forehead. While doing this the student is supposed to imagine him or herself as a soul and not as a body. The student is told to think of himself as separate from the body, as bodiless (asharlri), as light, as power, as bathed in the love and light of the Supreme Soul, and so on. This may continue for fifteen or twenty minutes or more.

What this procedure essentially involves is a visual interaction, in which there appears to be a kind of mingling of frames of reference. As an adept of raj yog the teacher has the power to "see souls." She has a "soul sight" (rihani or Itmik drishti), a frame of reference within which souls can be seen, and the object is for the student to come to share this point of view. That is, to know himself as a soul, the student must be able to see as the teacher can see; he (or she) must be able to see souls, where others see only bodies. The Brahma Kumaris conceive of this awakening of "soul-consciousness" as the opening of a third eye (here tZsra netra), located at the site of the soul, in the middle of the forehead.

In looking at the teacher, and seeing as she sees, one is, of course, seeing her as a soul, that is, seeing her as she sees you. And in fact this is more or less what happens, or at least what happens some of the time. While staring at the teacher many students, perhaps most, experience visual hallucinations in which lights seem to appear on or around the teacher's face and body. In my own case, a reddish halo would appear around her face, sometimes followed by an undulating red brightness overspreading her features. Others whom I consulted reported similar experiences, although there were individual variations. There is little doubt in my mind that these startling effects result from the action of the glowing red emblem on the eye in semidarkness, but this is really beside the point. What is important is that members of the movement have such experiences, and that such experiences are within the realm of plausible expectation, which in turn seems to rest on the assumption that a certain kind of "glancing" conveys a soul-power that is manifested as light, and also as the ability to see that light. Involved in this seems to be a conflation of "being seen" and "coming to see," in which one is changed-that is, one perceives oneself as more powerful-by sharing in a more powerful other's point of view.

There is nothing really novel in the Brahma Kumari concept of power. The idea of the third eye is quite widespread in the Hindu tradition (we have already seen it in Radhasoami doctrine), as is the concept of power being concentrated in the fore- head. The Brahma Kumaris also place great emphasis on celibacy, which is certainly consistent with the more general idea of sexual continence as a method of storing power, especially in the head. What interests us more is the apparent linkage between power and seeing and being seen. The Brahma Kumaris wish to become gods and goddesses; gods and goddesses are powerful beings, and in part their power takes the form of light. Thus, to be gods and goddesses, the Brahma Kumaris must be bright. The crux of the matter, it seems to me, is that to be bright one must be seen to be bright. That is, power is (as we would say) in the eye of the beholder, and therefore to become powerful, one must borrow a powerful beholder's eyes. In a Hindu milieu this is perfectly possible, because another's power of seeing, like any other power or valuable attribute, can be appropriated under the right conditions.

In the visual transaction I have described, there is something strongly reminiscent of the sociology of George Herbert Mead (1934). The goal of raj yog is self-transfor- mation; but truly to transform the self, one must create the self anew. The self, however, cannot create itself; it is, if one is to follow Mead, created only when ego makes an object of itself by learning to enter the roles of others. Mead, of course, emphasized the role of language ("vocal gesture") as the medium through which this happens. But there may be wisdom in the idea that the eyes speak a language of their own.

The learning of raj yog seems to me to be, in part, a process in which the making (or remaking) of self is simplified and formalized. One is supposed to renounce the old self, a renunciation made easier by the Brahma Kumaris' strong emphasis on be- coming "separate" (nyara) from worldly society; that is, on becoming disengaged from interactions in which one was "seen" in the old way. In what is, at least in theory, a vacuum of competing "points of view," one engages in the purest and sim- plest form of interaction-seeing and being seen-with a significant and powerful other. One's true self (that is, the new and more valuable self) arises as an object in her view, and by coming to share her point of view-that is, by seeing her as she sees you-this new self becomes an object for you as well. As one "takes in" a superior power-of-seeing, one is "drawn up" into a superior point of view. And, according to the Brahma Kumaris, having entered this new perspective one "sees" everything differently. One now knows one's true self as a deity-soul, and one now sees that the whole material world is, as the Brahma Kumaris say, only a "drama" to which the real self is but a "witness" (sakshi), as it plays its temporary role.

What I have discussed thus far is the teaching of rtaj yog as I experienced it in a movement center. But when one reaches a certain stage, the prop of visual interaction with a human alter is said to be unnecessary (although congregational yogic sessions are usually led by an adept); the teacher is finally only a surrogate for the Supreme Soul. What is then left is pure interaction, through inner sight, with the Supreme Soul, whose form is a pure point of light-power. He is the ultimate "other" to whom all raj yog is directed in the end. In this relationship there are strong echoes of themes I have already touched upon. In iconographic pictures the light of the Supreme Soul is often portrayed as streaming downward (sometimes fountain-style, in the manner of the Ganges from Shiva's hair in a well-known pictorial representation) to earthly devotees below. They, in turn, drink this light-power through their now opened third eyes. It is a subtle flow, pure divine power, to be visually imbibed by surren- dered devotees, who have their metaphoric counterpart in the moonlight-drinking chakor bird of Hindi devotional poetry.5 Moreover, it is said that the members of the movement are themselves the Supreme Soul's arati, because, as practitioners of raj yog, they know themselves as souls, which is to say, they see themselves as "lights" in the eyes of each other, but finally and most importantly, in the perspec- tive of the Supreme Soul.

more than one thing, but to the degree that it emphasizes seeing and being seen, it is a form of darshan. And if what the poet-devotees of the Radhasoami tradition say is any guide, similar principles are involved in gaze interac- tion between deities and worshippers in other settings. When devotee and guru "unite" gazes, a revelation is supposed to occur. The devotee, of course, must be "surrendered"; "egoism," the foundation of the older and to-be-discarded view of the self, must be banished. But if all is well, the devotee will embark upon an inward journey of the spirit, in which visual insight (among others) changes and deepens. Through the aperture of the third eye, an organ of transcendent inner sight, the dev- otee sees and is seen by the guru, and is "drawn up" to a higher plane, where he sees the guru, the world, and himself in, as we would say, a "new light."

My point is that, given the cultural context of visual interaction between deities and worshippers in India, there is an inner logic in the situation that makes intelligible the belief that the darshan of a deity or superior being is beneficial. This logic is usually implicit and unstated, but in the case of Radhasoami and Brahma Kumari teachings, it acquires an unusual, and I believe clarifying, explicitness. It depends on the idea that seeing itself is extrusive, a medium through which seer and seen come into contact, and, in a sense, blend and mix. Therefore, inner powers of the deity become available to the devotee, including, it seems, special powers of sight. The efficacy of darshan also depends, of course, on the worshipper/seer's own belief that there is indeed a powerful other whose visual awareness the worshipper has entered; a conviction that is probably powerfully buttressed by the worshipper's own awareness of himself as surrenderer, each gesture of homage being a further confirmation of the reality, superiority, and power of the deity.

Moreover, I think this interpretation is consistent with the common assertion by Hindus that the image of the deity is, finally, only an "aid." In tantric theory, in any case, it is held that objects perceived are actually in the possession of the perceiving mind

(Woodroffe 1978:87-88); and within the framework of such a theory, it is quite possible for a beneficial "other" to be generated by the self as a modification of itself. It may be, too, that in this instance indigenous and nonindigenous theories converge. That is, it may be that darshan finally and essentially is a way of utilizing the internal deposit of social experience as a way of changing and confinning certain special kinds of self-identity. In treating an "image" of a deity or guru as a superior being to be "taken from," the devotee may be simply realizing possibilities for self-transformation that are, whatever their origins in social experience, already internalized as part of his personality structure; creating for himself, and from him- self, a frame of reference that is superior to-and for the moment perhaps "realer than" (Geertz 1966)-all normal frames of reference. The deity would then be a point of focus for an internalized version of Mead's "generalized other," and darshan would be a powerful mirror with the potential to transform the viewer.